History of African Honeybees in the Rio Grande Valley

The Africanized Honeybees has been known as the “Killer Bee” since the 1960’s and became popularized in the 1970’s. Despite the alarming name, many Americans did not worry about the impact of the Africanized honeybee until the 1980’s.

The Africanized Honeybee began as a simple solution to a simple need: European honeybees were not productive honey producers in South America like they were in North America. Geneticist Warwick Kerr was asked by the Brazilian government to create a honeybee program to address the poor performance of honeybees in the Amazon basin and surrounding areas.

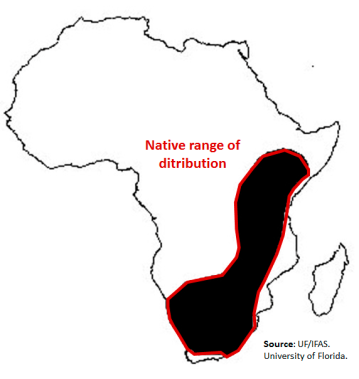

In 1946 an article from the South African Bee Journal reported record honey production from a South African commercial Beekeeper along with historical average production that far surpassed honey production in Brazil. The African Honeybee, Apis Mellifera scutellata, was well known for their highly defensive behavior and swarming tendencies. In order to make the African bee easier to handle, Kerr attempted to crossbreed two calmer subspecies of honeybee (A.m. ligustica and A. m. iberiensis) with the African Honeybee. A. m. lingustica, the Italian Honeybee, was the primary subspecies introduced to the Americas several centuries prior and to this day remains the most commonly worked honeybee in the world.

Kerr bred European drones, male bees, to 25 fully African bees from Transvaal and one African Queen from Tanzania. Kerr hoped that the African Queens would throw offspring as hardy and well-adjusted to the climate as her subspecies, but the calm genetics from the European drones would father more tractable hives.

Kerr kept the hives in his apiary near San Palo, Brazil while studying the results of the crossbreeding experiments. Beekeepers often keep devices known as “queen excluders” on their hives to prevent swarming. The excluder is a metal gate or mesh that only the smaller worker female bees can exit but prevents a larger drone or queen from leaving the hive. Many beekeepers that use these may take them off during a nectar flow, a time of year when there is an abundance of nectar producing sources in bloom) as the restricted entrances may make it more difficult for worker bees to leave and enter a door. Drones will often “clog” the doors creating a traffic jam. A visiting beekeeper saw the queen excluders hampering traffic and removed them without Kerr’s knowledge. African honeybees have higher tendency to swarm than European honeybees, so without the barriers preventing them, the Africanized hives almost immediately swarmed.

All Africanized bees found in the Americas are descended from those original 26 hybrid experiments in Brazil. Africanized bees are diverse in their European ancestry as they quickly interbred with the already established populations, but their matriarchal linage all come back to the original 26. African honeybees were well suited to South American, and they quickly reproduced. The high propensity for swarming meant that the African genes were not bred out despite how many commercial beekeepers kept hives in Central and South America.

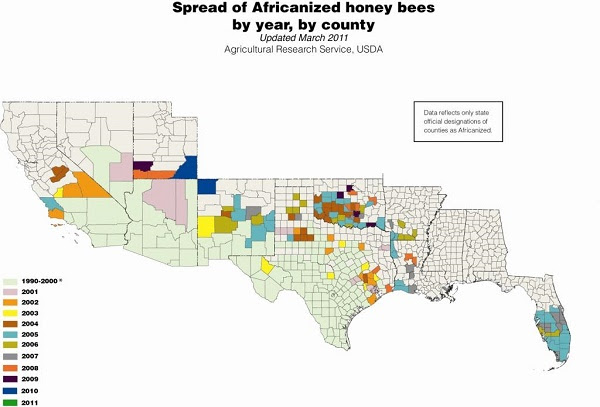

Africanized Bees spread throughout South America at an unexpected rate, making its way to central America by the 1980’s. As they traveled, beekeepers, scientists, and laypersons alike speculated on how far the African bee could spread. By the 1970’s people had started to fear the “African Killer Bee” thanks in part by a campaign by the USDA.

Beekeepers and researchers set up swarm traps and testing facilities to track the spread of African honeybees. The first African bee swarm found was in Hidalgo county in 1990’s. This scared people who worried about being killed by these “aggressive, killer” bees. Beekeepers either gave up their hobby after a few years or commercial beekeepers relocated further north.

The first Africanized Honeybee death recorded in the RGV, and the US, was when an elderly farmer attempted to burn an abandoned building after discovering it had bees in July of 1993. The bees subsequently attacked the man and he succumbed to a venom overdose. A scientist from the USDA bee lab in Weslaco, Texas had to exterminate the hive and took samples back to his lab to confirm the bees’ African genetics.

Since then, African bees have spread across the country. Roughly 2 people die every year from venom toxicity after being attacked by bees. More people die from simple allergic reactions from a singular bee sting. Hospitalization due to bee stings are more common, however the fatality rate has typically remained very low.

While beekeepers have since learned how to work with, rather than against African bees, public fear remains high. While these bees can be dangerous to the inexperienced, they are not exactly the tiny murderesses they are made out to be.

- Share: